PIANC and Corps Advocate for Sustainable Marina Planning

Published on May 4, 2020Sustainability is not a new concept in marina design. The idea that environmental, social and economic benefits all work together to inform project design has long been touted as a smart way to do business. However, businesses are more often driven by economics, and regulatory demands have often been considered an environmental cost of doing business. That approach can drive projects off a balanced course for sustainability – with too much concern over project economics; designing projects solely to meet regulatory standards; and creating spaces that provide for boaters but not the general public. Truly sustainable projects should find the best synergy between all three. Additionally, environmental concerns and limited waterfront space puts more pressure on developing projects with wide support.

Part of the problem in the world of marina design is how and when the regulatory process informs project design, not necessarily the specific requirements. The main goal of environmental impact assessments (EIAs) has always been to produce a better project for the environment, considering natural, social and economic components. According to Esteban Biondi, associate principal at Applied Technology & Management (ATM) and chairman of the PIANC (The World Association for Waterborne Navigation Infrastructure) Recreational Navigation Commission, the way the EIA process has been typically used in the design process, doesn’t simultaneously consider all the elements – instead, first the design, then do the EIA analysis, then try to mitigate for impacts.

“The problem with that is that you only incorporate environmental issues seriously too late,” Biondi said. “By the time the environmental impact information is available, too much time and money has been spent in developing the design and there is less opportunity to make meaningful improvements.” The problem can also be exacerbated by separate consulting groups doing the design and environmental analysis with little communication between the two.

Working With Nature

PIANC’s Working with Nature concept was first discussed in a position paper in 2008: “Working with Nature is an integrated process, which involves working to identify and exploit win-win solutions, which respect nature and are acceptable to both project proponents and environmental stakeholders,” the paper said. The concept was not meant to replace the EIA process but enhance it, Biondi said.

The Working with Nature concept advocates the following steps:

• Establish project needs and objectives;

• Understand the environment;

• Make meaningful use of stakeholder engagement to identify possible win-win opportunities;

• Prepare project proposals/design to benefit navigation and nature.

“These steps may seem trivial, until you realize that these simple steps are not followed in too many cases. Of course, this is not an administrative compliance check list: considering them deeply as a design approach philosophy is needed to get results with significantly better outcomes,” Biondi said. For marina projects, he said it’s often about “asking the right questions” early on in the process.

Engineering with Nature

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers embraces a similar approach and fully compatible initiative, which it calls Engineering with Nature®. It defines this initiative as: the intentional alignment of natural and engineering processes to efficiently and sustainably deliver economic, environmental and social benefits through collaboration. Engineering with Nature seeks to utilize natural processes to maximize benefits, and focuses on involving other stakeholders and partners for science-based collaboration.

The Engineering with Nature initiative considers several design elements alone or preferably in combination, including:

• natural features – biological, physical, geological and chemical processes operating in nature over time;

• nature-based features – mimic characteristics of natural features, but are created by human design, engineering and construction;

• built components – namely manmade structures of concrete or steel (“gray infrastructure”), but can also include nature-based features (“greening the gray”), such as texture on a seawall for habitat;

• non-structural measures – policy, building codes and land use zoning.

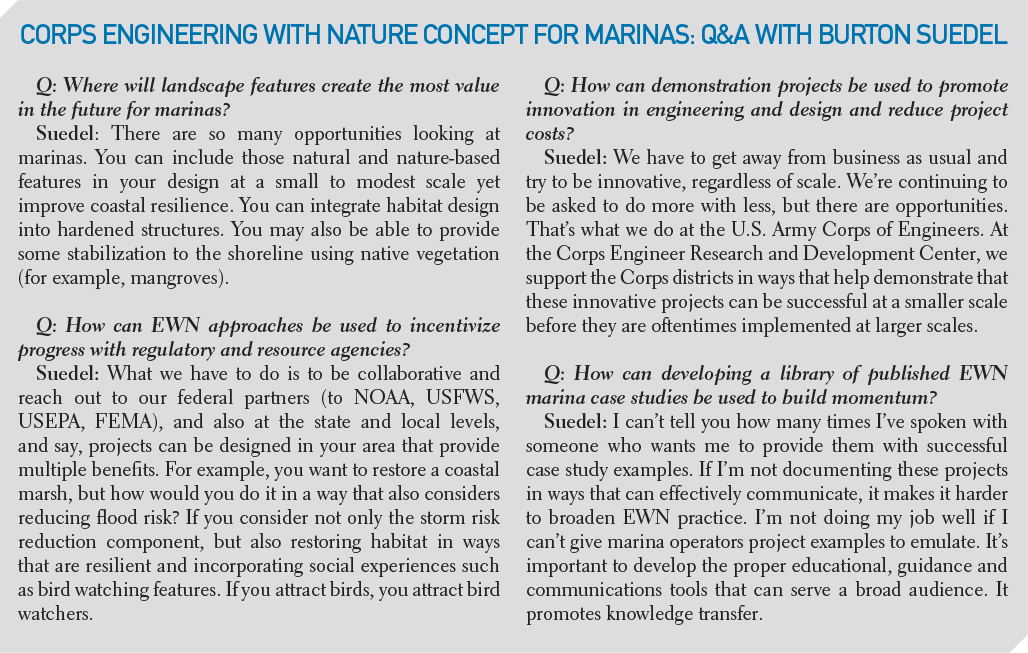

Burton Suedel, Ph.D., research biologist with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Engineer Research and Development Center (ERDC), points to Fort Pierce City Marina in Florida, as a good example of how Engineering with Nature principles were implemented in practice. The project has many ecological benefits (living shorelines, natural limestone armor reefs, tern roosting areas) and big economic benefits from increased marina and tourism revenues.

“They also obviously did a great job of talking with a variety of stakeholders at the state, local and city level,” Suedel said.

In 2018, the Corps published the first Engineering With Nature Atlas, a collection of 56 projects that integrate natural processes into engineering strategies. Now, the Corps is compiling volume two of the atlas. Suedel said the Corps is on schedule to release that later this year. It will include a highlight of the Fort Pierce Marina project.

For more on how the Corps Engineering with Nature initiative can be incorporated into marina design, see the sidebar on page 8.

Beneficial Use of Dredged Material

Dredged material is an environmental concern for many marinas on a regular basis, and one that continues to drive study and innovation. In 2009, PIANC published, “Dredged material as a resource: options and constraints.” The working group developed guidance on future considerations for the use of dredged material on a routine basis. It identified obstacles to and solutions for integrating the use of dredged material into navigation projects.

Victor Magar, Ph.D., P.E., of Ramboll, is part of a working group revisiting that document and updating it. The committee will finish writing the document this year, and PIANC will publish the new guidance in 2021.

“We’re advocating for more beneficial use, trying to bring more ports and navigable waterways and dredge managers to recognize the value of beneficial use,” Magar said. One of the biggest challenges for beneficial use, he said, is finding creative local uses for sediment and getting regulatory approval. Common uses include wetland creation and restoration; flood control and coastal resiliency; and brownfield redevelopment. More local uses can include agricultural, transportation, infrastructure and landscaping uses. Like all sustainable design, plans for beneficially using dredged material must be considered from the outset of project planning.

Case Studies

Working with Nature and Engineering With Nature based designs incorporate multiple-function solutions, such as living shorelines, mangrove islands and boardwalks and kayak trails. Biondi has worked on many marina projects that incorporate mangroves in different ways – although it is not new to marina design, it is often a forgotten approach. Biondi points to several projects in Florida that showcase mangroves integrated into the marina design. At Harbourside in Jupiter, Florida, the design incorporates natural mangrove edges in an urban waterfront setting. The project provides access to docks, public space and natural shoreline with mangroves. The water’s edge was developed by retaining the existing mangrove fringe and incorporating it into the landscape and shoreline design. This project also demonstrates a great example of mangrove window trimming, which provides views and shade in the public spaces.

At Admiral’s Cove in Jupiter, Florida, mangrove edges line the residential canals and the yacht club. The Admiral’s Cove Marina is part of a high-end residential community, and the private club has been around for three decades. A mangrove wetland forms the edge of the marina at Jupiter Yacht Club in Florida. The private marina combines with a public promenade and marina village. Jupiter Yacht Club was built in the late 90s around an existing mangrove wetland.

Suedel said that marina projects implementing such designs are realizing multiple benefits through applying nature based solutions in practice by integrating habitat into structures, using natural and nature-based features to support coastal resilience, and stabilizing the shoreline using native plants.

Social Sustainability and Guest Experience

The newest element of sustainability for designers and developers to embrace is the social aspect. For marina projects, social sustainability can be justified in different ways, depending on the specific project characteristics. It applies both to a project within urban communities that can derail permitting, or in some developing countries where the community has no voice of influence. The underlying justification is that looking at community and social issues can add value to the marina project.

Biondi said that he has been considering these issues for almost two decades, testing ideas in multiple projects worldwide and writing papers. He perceives that now the rationale for win-win solutions and the hospitality industry best practices that influence marina design are converging.

“In the last 10 years, people have started talking about experiences,” Biondi said. “If you look at that analytical approach to value and you take into account that the local community has the potential to deliver authentic and memorable experiences, that has a huge economic value from the point of view of tourism.”

When a project creates a space within the marina for the local community to bring in some services that showcase its culture and history, the project gets value and the business directly benefits from the local community, Biondi said. The economic benefit works for the marina development too, as boaters and tourists are looking for authentic experiences.

“Solutions depend on local circumstances, but we have proposed activities, such as sea-to-table programs, fishing charters or marine tours to be operated by local community entities, with specially designed and themed spaces for this purpose,” Biondi said. “We know that the most challenging work is in the detailed implementation of the programs with the local community, which are sometimes undertaken by foundations or concerned individuals, but if the master plan does not have a space reserved for this purpose, what is already difficult becomes impossible.”

| Categories | |

| Tags |