Is the Goal Wave Attenuation, or is it Harbor Tranquility?

Published on February 24, 2021Editor’s Note: In the April 2021 issue of Marina Dock Age, Jack Cox will focus on how to design a marina to achieve tranquility.

In past issues of Marina Dock Age there have been several fine articles about wave attenuators, and the need for wave attenuation. By now we know that when talking about wave attenuators, the first thing we need to ask about is what sort of wave periods are we dealing with, not just how big are the waves we are addressing. It is true, in some ideal situations, that the height of a wave can be correlated with a period of the wave, but to do that you need all sorts of perfect conditions with the right combinations of wind speed, fetch distance (the overwater distance across which the wind blows), the relative direction of the wind, the duration of the wind blowing, and even the water depth where the wind is blowing. That rarely happens since usually you never have all those perfect combinations of factors. Something is different which changes the wave height or throttles the wave period. A wave climate is not so easily characterized by just stating a wave height value and you should not be fooled by someone purporting such elemental thinking. You need to include an understanding of the site as well – and that, inevitably, means figuring out the wave period. That is a hard thing to do.

the wind is blowing. That rarely happens since usually you never have all those perfect combinations of factors. Something is different which changes the wave height or throttles the wave period. A wave climate is not so easily characterized by just stating a wave height value and you should not be fooled by someone purporting such elemental thinking. You need to include an understanding of the site as well – and that, inevitably, means figuring out the wave period. That is a hard thing to do.

So, let us step back and re-ask the question in this form. Do we really care how big the waves are out there, or are we really more concerned with just how calm our marina is? That is what your customers care about. So, how calm would we like our marina to be? If you have heard me address this in the past you know there are a bunch of answers. Here are a couple:

“I want the waves to be no more than 1 foot.” So, what is the basis of that criteria – well it is simply that 1 is the smallest whole number there is until you get to zero! That is just one of those gut opinions offered long ago with no further justification, other than it seemed to work, that survives until today. What do you suppose the equivalent of that standard is in Europe, which is on the metric system – 0.3048 meters? (That is the conversion of a foot to a meter for those of you who do not want to do the math) No, they just say 0.3 meters so already we have a difference of opinion depending on whether you live in an English unit or metric unit world.

“I want my marina to be calmer than my competition’s so all the boaters will come to me first.” Now that is a real and fair criterion, but it is tough to design to unless you go visit all the competition and then decide what you want yours to be. By the way, we call that criteria the “New England” criteria as those sailors are real tough guys and can handle those rough seas.

Then there is the California criteria. “When the sun is setting and I’m sitting in the cockpit of my boat, I do not want to spill my martini if a wave goes by.” There actually is some serious implications and insightfulness offered in that criteria. We will touch on this later, but it still does not give us a number to design to.

“Good” Wave Climate

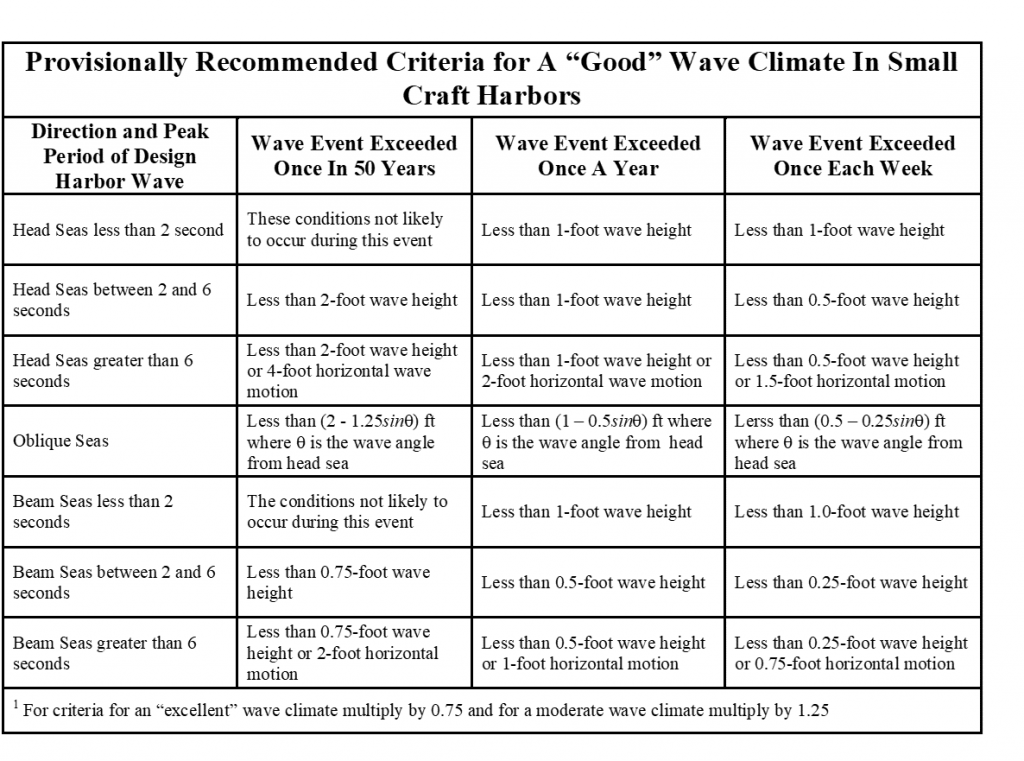

Leave it to the Canadians to actually figure this out. In some research conducted back in the early 80’s, a study focused on exactly the California criteria, but in a more rational form. The study looked at how rough a wave condition needs to occur to induce certain risky behaviors on or by the boat. To do this, they studied how the boat might be moored, how often the event might happen, and even what was the risk level and consequences if the agitation did occur. The latter might be anything from someone being bucked off a dock, to sailboats rocking and cable stays becoming entangled, to actual rubbing and crushing of boat hulls with the dock. They discovered some interesting realities, which have some profound implications.

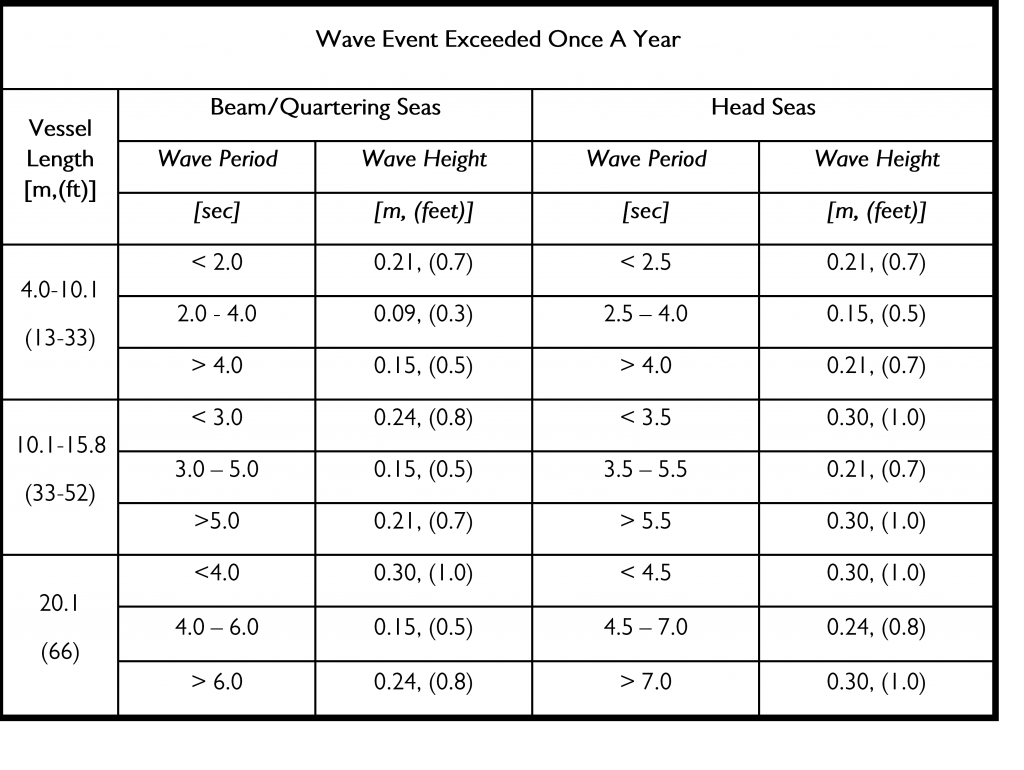

Shown here in the table is the conclusion of their findings. Note that the table recognizes three factors, the PERIOD of the waves, the relative ORIENTATION of the boat to the wave direction (head or beam seas) and the FREQUENCY of occurrence, or return period, of the offending event. The category for oblique seas is a recent addition to the original guidance that has been added by this author.

First, we notice that it seems to be okay if we have worse agitation during times of severe storms as they happen less often so the risk of pushing out tolerances a little higher is acceptable, as long as we are still within some safety range.

If we look at the numbers more closely, the next thing we notice is that the criteria is not just one number but ranges from as little as a quarter of a foot to over 2 feet! How can this be? Well, the simple answer is because the boat is floating! What a surprising reality we never thought about. Unlike buildings, which are rigid, a free-floating object is just that. It can move up and down or twist and turn, all depending on what is pushing against it. The table suggests to us that if wave periods are less than about 2 seconds, that the boat stays pretty much stationary in the water, and the waves just bounce against it. At the other extreme, at 6 seconds or above, the boat is not necessarily stationary, but becomes largely a surface follower, moving up and down with the wave, so again, not necessarily a big issue as long as everything is moving together.

It is that 2 second period to 6 second period that is the problem child. Why? Well, it also turns out that most boat and barge shapes have a natural heave and roil period (that is moving up and down and rocking side to side respectively) of 3 – 5 seconds. This is true for even large floating objects, though we might be surprised to think a large barge would react to a short little 3-4 second period wave. As an illustration, if we look more closely at a tranquility criterion for a yearly type of event – what Mr. California wants to see. Now you can see that the specifics get down to the boat size level, but regardless, the criteria is most restrictive if waves are in the 2-6 second range.

As an aside, this table also gives us some guidance of likely what sort of criteria we should aim for at boat launch ramps. For typical trailerable boat sizes, we would want waves no bigger than in the 4-6 inch range, depending on the orientation of the launch.

In the sensitive period range, when these floating objects get excited by the waves they become activated and start to move on their own. Under the right circumstances, they actually can move more than the wave is moving. Now here is the kicker. When we look at wave formation in most boating (non-storm) climates, we unfortunately find the waves have periods of 3-5 seconds, right where the boats are most susceptible to becoming agitated. Hmmmm, maybe Mr. California was on to something when he was worried about spilling that martini. So, our challenge is then how to create a marina that meets goals such as the Canadians recommended.

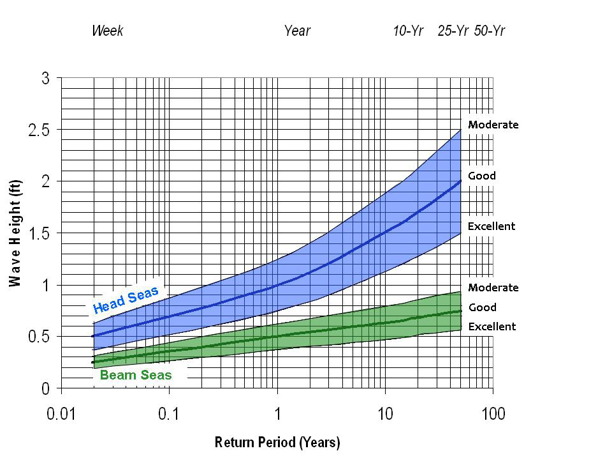

For this, the Mounties also come to the rescue. The third thing they recommend is that there is a huge difference in what would be considered allowable in a beam sea versus a head sea. The table shown on page TBD is repeated here as a graphic to help show the application.

If you compare the difference between an acceptable wave height, for a given wave period in a head sea, you will find that it is nearly three times as large as for a beam sea. Wow. That has huge implications. Why the difference? A boat is long and narrow and is designed to slice into the waves with little movement when going ahead. However, if a wave slaps our boat on the side, it has a much greater tendency to roll. So, we can accept more wave action if it comes at us head-on than from the side, while achieving the same level of comfort.

So, what can we do with that new information? It turns out, a lot. It says that we can conceivably achieve the same acceptable agitation level from a smaller wave attenuator or breakwater if we look at a marina as a system considering how the docks are laid out. How often do we do that? I am guessing almost never as we default back to the old way of doing things by running all docks out from shore as individual piers. That just about guarantees that the boats in the slips are always moored as a beam sea – the worst possible orientation.

If we take advantage of this knowledge about desired berthing tranquility, we could build a breakwater that might be a couple feet lower, or an attraction that is smaller or requires less draft, and, going all the way back to the docks themselves, maybe we do not even need as many piles if it is just the waves that cause the worst loading.

These are all the things we want to think about early as we plan a layout for a marina. We need to see the entire marina as working together as a system to give us the best package for the least cost. We should not just assume we need a certain amount of attenuation, but rather an acceptable tranquility goal and then work backwards considering the marina layout, and then finding a corresponding wave attenuation system that will give us that goal.

| Categories | |

| Tags |