Smart Marinas: Scanning What Lies on the Horizon for Higher-Tech Recreational Boating

Published on January 12, 20212020 was an unusually eventful year, so some developments that would otherwise have captured more attention are still waiting to be unpacked. This was partially the case for the new milestones being set for the integration of technology with marina operations and management. Some of these pioneering moves are getting good coverage and recognition. At the same time, the overall course these innovations appear to be mapping out towards the higher-tech “marina of the future” tends to be more uncharted.

One of the big marina tech stories of 2020 was Gulf Star Marina in Fort Myers Beach, Florida opening what they describe as “the world’s first SMART marine storage facility.” Featuring fully automated storage and retrieval (ASAR) technology that is also transforming automobile industry and warehousing operations, Gulf Star’s new drystack facility gives them greater storage capacity and launch/retrieval efficiency in a highly hurricane-resistant structure; it also allows them to promote a new level of integrated customer service and convenience. Per their website:

This high-tech system will enable us to put your boat in the water in just seven minutes … Additionally, we provide concierge level service at every turn! That includes soap wash top side, engine flush, rub rail scrub down, service request noted, and cover.

Following years of proven operational success with The Port Marina’s touchscreen, computer-controlled bridge crane system, which cut the launch and retrieval cycle to 25% of what it was previously, F3 Marina is scheduled to open its second automated drystack storage facility in Fort Lauderdale later this year. While the costs and benefits of automated systems vary based on the technology and manufacturer, these two examples reflect the growing trend of computerized automation and connectivity within the industry, pointing towards the aspirational idea of the “smart marina.”

These new directions raise important questions about what it means to define marina infrastructure and operations as smart, and when it makes market and economic sense for marina owners and operators to embark on a more technology-driven course for their facilities.

SMART Versus Smart Marinas

The use of all caps for Gulf Star Marina’s SMART storage facility represents an important distinction in how that term is applied. SMART is a computing term that stands for “Self-Monitoring Analysis and Reporting Technology.” The acronym was developed in 1992 for a technology that enabled computers to monitor the health of their own hard drives and alert owners about any problems.

Use of the word quickly expanded to encompass any innovative device that was computer-enabled – from the first interactive whiteboard, the SMARTboard, to the first computerized cell phone. Today it is easy to forget how revolutionary putting a microcomputer in a cell phone was, but it also played a major role in broadening the use of SMART. The term smartphone was coined sometime around 1992 and became part of the product’s official branding and marketing by 1995. Since that time, what “smart” means has continued to change and evolve along with computer technology itself.

When referring specifically to technological innovation, both SMART and smart encompass the idea of digitally networked and interconnected systems.

These systems are increasingly leveraging developments in artificial intelligence, machine learning, the Internet of Things (IoT), and enhanced data access and processing to push past self-monitoring to nearly fully autonomous physical operations. From the automated drystack systems highlighted above to emerging applications for autonomous/self-driving vehicles (including boats), smart technology is aiming not only for automation but also improved performance through processing of real-time data on operating conditions and outcomes.

As the scale of smart-system application increases, so too do the parameters of what “smart” means. This is especially evident in the emerging Smart Cities trend for urban planning and design. While some Smart City advocates emphasize a definition centered on electronic methods for collecting data and using that data to manage city resources and services more efficiently, others have adopted an expanded definition similar to this one in Business Dictionary:

A smart city is a developed urban area that creates sustainable economic development and high quality of life by excelling in multiple key areas; economy, mobility, environment, people, living, and government.

Quality of life and quality of environment/place play a critical role in this expanded definition of what makes a city smart. While the future is still technology-enhanced and data-informed, optimizing the use of new technology is only part of the vision for what is needed to benefit a city’s residents and improve their lives.

In addition to emerging Smart Marina/Smart City practices in Europe, another model that is relevant for the marina industry is the framework for Smart Ports being advanced internationally in Rotterdam and other major port cities. While SMART systems for port operations and infrastructure are a critical part of the mix, there is also thoughtful consideration of clean/renewable energy, environmental enhancement and protection, improved security, climate and disaster resilience, the development of new port-oriented economic and employment opportunities, and improved community connections.

When considered within a larger Smart Marina framework, technological innovation is not the primary end goal but a means to more sustainable economic performance for the owner and an enhanced experience for boaters and visitors. Improved environmental stewardship is also a key consideration, given the industry’s reliance on water and environmental quality for its recreational and locational appeal. The extent to which technology-enhanced and automated operations could benefit a particular marina can be better assessed within this broader site- and market-specific framework.

How SMART is smart for your marina?

New marina developments, as well as marinas that are looking to upgrade or redevelop their facilities, will be facing many questions about technology adoption moving forward, often without established precedents to draw on. Determining which facets of a marina’s infrastructure and operations can benefit from integrating new technology will become an important part of business planning. Drystack automation is certainly one aspect to explore for markets where the required level of investment makes competitive financial sense. For many U.S. markets and marinas though, integrating this technology might not pencil out.

How can you evaluate whether a smart system is right for your marina, your market, and your revenue/investment stream? What is the cost/benefit of adopting new technologies – especially as an early adopter? How can owners and operators maximize the benefits of smart marina systems without overinvesting or locking into something that can’t be effectively upgraded or adapted later?

Our upcoming Water Marks articles will take a closer look at emerging high-tech options for marinas in three broad categories:

• smart infrastructure – including the world of automated drystack storage and the use of sensors to monitor and improve marina performance and environmental outcomes;

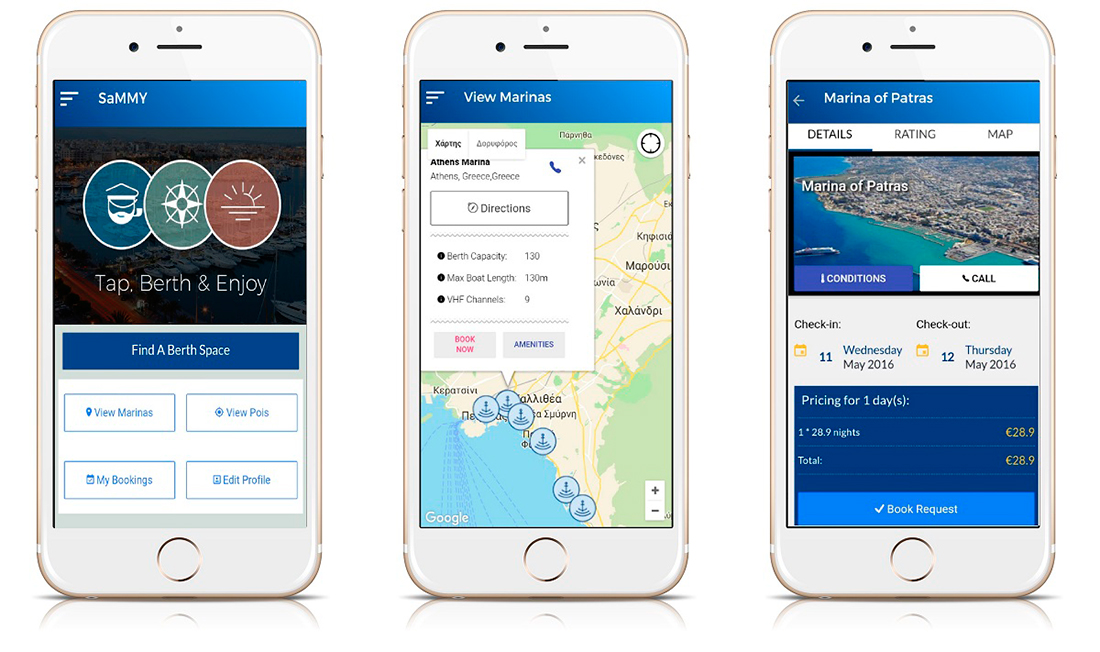

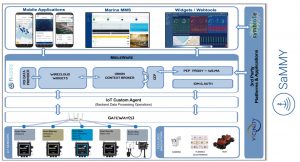

• smart administration and operations – with opportunities to deliver services and communicate with a new generation of customers more efficiently and effectively; and

• smart boat and navigation/docking systems – and the implications for expanded and more sustainable water-based mobility and tourism.

By exploring new technology systems as integrated practices as well as game-changing products, marina professionals can start to lay out an effective course towards Smart Marina development from a wider range of launching points.

Jason Stangland is waterfront practice director and David Lantz is waterfront practice manager for SmithGroup. They can be contacted at jason.stangland@smithgroup.com and david.lantz@smithgroup.com

| Categories | |

| Tags |