The War Room

Published on January 13, 2025If you search for “The War Room” on Google, the top three results that appear include a 1993 documentary of the same name about the 1992 Bill Clinton U.S. presidential campaign; Steve Bannon’s current War Room podcast; and a 2015 Christian movie called “War Room” about how the power of prayer can help heal a family.

When it comes to operating a marina, a “war room” comes to mind when a facility ends up in battle, particularly a battle with a regulatory agency, an unhappy neighbor, a citizen group or some similar adversary. That battle can lead to the marina’s team gathering in a real or virtual room to work out strategies and options for getting through the issue. It’s a room no one wants to be in, but it’s worth thinking about before you find yourself in the thick of it, including who you would have or need to have in there with you.

We have a great deal of respect for regulatory agencies that have a job to do, as well as neighbors who might be resistant to change. Honest people can have honest disagreements. Talking things out early in the process and understanding the various perspectives can often lead to very desirable, cost-effective and timely determinations.

But, for better or worse, we live in an increasingly litigious society, regardless of whether there is merit to lawsuits. Adding to the complexity are the regulatory world’s hurdles becoming more and more difficult to overcome, and the approval process becoming so densely bureaucratic that it is increasingly easy for an adversary to challenge even issued approvals.

Having Knowledgeable Support

We happen to know of a perfect case in point where an agency made a mistake in the process of issuing an approval, and someone from the public subsequently challenged the decision. It involved a relatively small, family-owned marina that had done everything the agency had requested, received its approval, and went ahead and built its expansion. The approval was then challenged by a distant neighbor who had a longstanding history of launching legal attacks against the marina, hoping to make it go away. The marina initially turned to a family lawyer, which is quite common in such instances, who

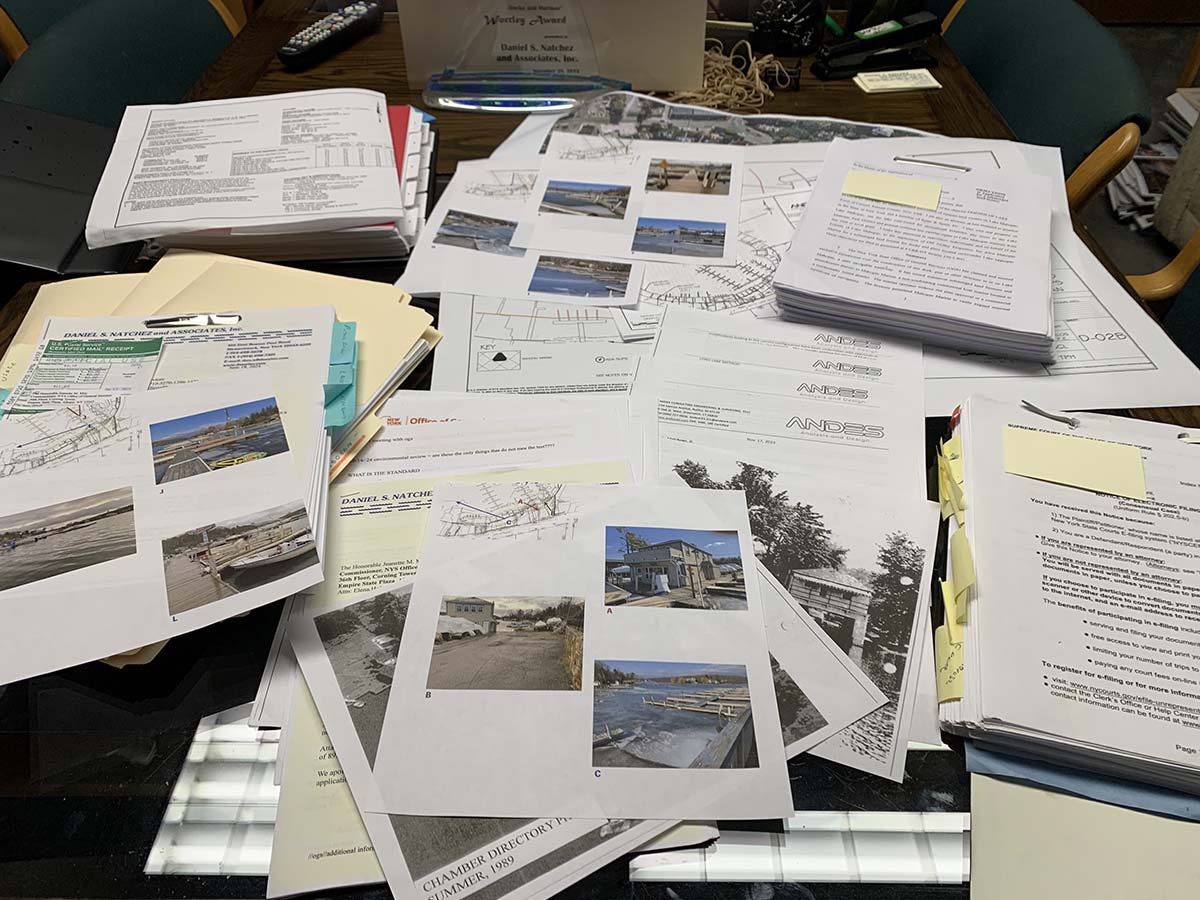

Site inspections help to determine infrastructure updates, including floating docks that house ship’s stores and other amenities.

entered the case on behalf of the marina. Unfortunately, this type of situation was not the expertise of the family lawyer, and the marina had assumed that the state agency could make the case in defending its issuance of the approval. Bottom line, the agency did not rise to the occasion, the family lawyer, while earnest, was a bit out of his element, and the court’s decision went against the state, which then invalidated the marina’s approval. This is a worst-case scenario, and the result was that the marina had to start the approval process over, this time making sure that both it and the agency dotted every “I” and crossed every “T.” This time the marina also set up a more robust war room, bringing in a knowledgeable marina consultant and, in turn, a legal team with the right experience.

Hindsight is always 20-20, or at least a lot closer to it, but one of the morals of this story is to do all you can to make sure all is correctly undertaken in the application process, even if the agency needs to be led. While it takes time and likely costs money up front, it can save a great deal of problems and much greater expense later.

Of course, no one wants to get to the point where a war room is needed, particularly a fully lawyered-up one. There are ways to help you not get there, beginning with always doing your homework.

There really are no shortcuts to doing your homework. Start at the beginning to understand the site’s advantages and challenges and whether what you have or want to do complies with or deviates from the programmatic perspectives of the agencies, both promulgated and unpromulgated.

Other items typically include undertaking meaningful and thorough hydrographic and upland hydrographic surveys of both the project and abutting properties, looking at the various state and federal mappings for not only regulatory lines but designations for endangered species, waterfowl migration areas, sensitive habitats, subaquatic vegetation, mapped and/or perceived navigational lanes and view lines from all angles. Understanding the history of the site and surrounding areas, the community master and other development plans and programs for the area and talking with the neighbors as well as local environmental, conservation and civic groups are especially important.

Many times, there is hesitation about talking with the neighbors and others for fear of tipping them off, creating a problem and/or activating a concern, but most of the time these discussions can help pave the way for the project and avoid costly delays and other problems. People in general react to how they are treated. The project will become public, and the neighbors as well as “involved” citizen groups will typically be formally notified. Preempting the notification with personal contact and discussion, including a review of your concept site plans, can go a long way to defining, identifying and potentially defusing various potential hurdles and issues. Often, the identified concerns can be dealt with through relatively minor project modifications, which also will be easier to make before you go too far down a different path. Even if there are issues or concerns that can’t be accommodated, whether irrational or not, knowing what they are and who the protagonists are is helpful. The sooner you know how big a war room you might need, the better.

Understanding the Issues

Knowing the issues will also be helpful in preparing for presentations and discussions with all the agencies. Review all of the concerns including those raised by others along with the alternatives that were considered and determined not to be viable.

Similarly, once homework is complete, the initial project concepts may need to be refined to either meet the identified regulatory parameters or to have significant justification for the deviation from the programmatic desires, as well as all the mitigating factors for the project area, including for the environment. It is important to address the deviations from the programmatic approaches and the unresolved concerns by others up front, including why they are being proposed and what the justifications and benefits are. This helps put potential issues into perspective and create a more desirable mind set.

Working with the agencies at the very early concept stages goes a long way to achieving the approvals on the desired project or very close thereto.

However, there are times that some individual(s) in some agencies can be a bit more cantankerous and difficult to work with. At that point, some agencies may take the position that they never make a mistake and circle the wagons. Even in those circumstances, there may be ways to work through the process with a meaningful result and avoid the war room.

In one instance, a regulatory agency made a site visit for a project that included rehabilitating a damaged but still functional seawall that had professionally prepared survey plans showing that the Mean High Tide line was significantly below the top of the seawall, and the wall itself had water stains clearly showing the high tide being well below the top of the seawall.

The plans were stamped by a licensed surveyor and engineer, yet the agency sent a letter stating that the seawall was no longer functional and that there was significant daily tidal inundation of the upland well beyond the seawall.

It turns out the agency had made its site inspection just days after a substantial episodic storm, with considerable flooding of the entire coastal area, including the site, sending flotsam and jetsam well into the upland. The agency focused on the remnants of the flooding rather than the actual facts, elevations and drawings. Instead of just admitting a rush to judgment, the agency insisted on the site being resurveyed and for the applicant to provide additional justification for being able to repair the seawall. When the agency came back to the site with the updated plans, representatives were able to agree that the seawall was functional, and the tide did not cause daily flooding.

In another instance, a marina wanted to put a fuel station/marina office/store building on a floating dock. One regulatory agency said that the fuel station/office was a structure in a FEMA zone, and you cannot put a structure in the FEMA zone because it floods. The reviewer did not understand that the float would rise and fall with the water, and, therefore, would always be above the water and was permissible under FEMA, so long as it had an adequate anchoring system.

Of course, there may be times when an agency simply will not agree. If the project makes sense and has major givebacks and justifications, and an agency is going to deny the project as presented, there usually is an appeal process of going to a hearing. In one such case, we were working with a marina that wanted to expand. Despite all of the documentation that was presented, the reviewer basically came down with either change, including substantially reducing the project, or go to hearing. Due to all of the homework that had been undertaken and the major justifications of the project refuting the reviewer’s perspective, the marina elected to go to hearing. The hearing was scheduled for two days. We presented the project for about 45 minutes, documenting every step of the way, including what the agency’s objections were and what were the mitigation factors and givebacks, with everything being documented with clear and clean exhibits, including highlighting the significant mitigation approaches and the fact that the alternatives to the project, including reducing the project, would eliminate the major environmental benefits. The agency then presented its objections for about 30 minutes. The hearing lasted another hour, with the rest of the hearing being members of the public who came, speaking in favor of the project. They were the same people whom we talked with early on in the concept phase. At the end of the hearing, the officer rendered a favorable opinion on the project and directed the agency to issue the permit.

So, whenever you find yourself approaching a project, whether for a new marina, an expansion, reconfiguration or even substantial repairs these days, it just makes sense to approach it as if there will be some opposition. Doing one’s homework and using experienced professionals to help guide one through the process are meaningful suggestions.

Dan Natchez, CMP, is president of Daniel S. Natchez and Associates Inc. He can be contacted by phone at 1/914/698-5678, by WhatsApp at 1/914/381-1234, by email at dan.n@dsnainc.com or online at www.dsnainc.com.

| Categories | |

| Tags |