Understanding Agreements and Delivered Products

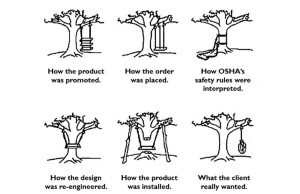

Published on August 21, 2024How many times, when dealing with a vendor — whether a supplier, a contractor or even the designer/architect/engineer who is supposed to be on your side – does there seem to be a mismatch between what was originally intended and the delivered product?

How do you achieve an understanding between intent and delivery? The pathway can include one of two types of specifications. One is a detailed specification that defines everything down to the last nails that are needed to go into a project. If you take that path, you must know exactly what you want, prohibiting any variation from that, and you must be explicit and leave nothing to chance. At the other end of the spectrum, you may have a performance specification. In this case, all you care about is how it will do its job. If you just want a door, what it looks like, smells like, or how big it is may be unimportant if it closes to cover an opening. More than likely, you will add a few more details, like it needs to be wide enough and tall enough to walk through, or maybe it is fireproof, etc. This might seem simple enough, but let’s look at that last requirement – fireproof. This requirement can include a few details, such as how long does it need to not burn or how long it takes to burn through and does it matter if it emits fumes, possibly poisonous, when exposed to flame?

Even performance specifications can be detailed and complicated. Most of the time the path taken is somewhere between these two types of specifications. In some areas we give more detail than is needed, which inadvertently dumps risk back on us by requiring things that may not be the best choice. Sometimes we don’t specify enough, leaving the door open to legitimate “interpretation” that may land you somewhere not intended, even though it works.

Discovering the Landmines

For example, suppose I want to build a dike, flood wall or breakwater. I do all my fancy calculations and compute that it should be 10 feet tall. I create a drawing and say to build it 10 feet tall. Now, something called constructability comes into play, especially if I am building with rock that results in an irregular surface, with high and low spots because of variable sizes and shapes of the rocks plus the voids between. So where is my 10 feet measured to, the top of the tallest rock, bottom of the rock, some mean value, and must that be a constant line?

Surprisingly, the contractor will choose to answer that based on what kind of contract you have solicited from him, not necessarily how you assumed or intended it should be interpreted. Remember, his goal is to make as much profit as he can, while still being legitimately within what specifications you provided.

Any construction document allows some sort of construction tolerance. Even when you lay down a hardwood flooring, there is guidance that says the boards can have a gap of about 1/32 inch, and similarly the relative height of each board compared to the board placed next to it might be allowed to be 1/16th inch different. If you develop a crack in a wall, the contractor may not have liability until it opens to 1/8th inch or similar. Since construction is rarely completed in a perfectly straight line, tolerances are allowed everywhere. With coarse grade construction, especially with placing rock, those tolerances are typically in the range of +/- 6 inches. In total, you are allowing 1 foot of variability in 10 feet of height, or a possible 10% difference between what you intended versus what you are allowing the contractor to build.

Deciding on a Contract

If you have asked the contractor to give you a firm, fixed price, which tolerance line do you think he will try to build to? He will likely pick the lower line, so he uses less material. If you ask for a time and material, or unit cost contract, he will try to build to the highest tolerance, so he gets more fee. Both are legitimate responses, but you probably computed that you needed the full 10-foot height to block the water, so how do you write your specification to get as much protection as needed without spending more than is necessary? That becomes the challenge to the engineer as to how to achieve the performance needed for the least investment required, and you can see that trickles all the way back to what kind of contract is involved.

Ordering a wave attenuator can also backfire if enough detail isn’t included in a specification to a vendor. The controlling parameter in a wave attenuator working is the wave period, not the wave height. But the wave height is the thing you can see, and it is more easily measured, so if you just say you have a 3-foot wave, and you want to get it down to less than a 1-foot wave at your dock, then that is the performance criteria you mistakenly provide.

Unfortunately, any attenuator can do that if you have not also specified at what wave period it must occur. The vendor is not lying to you. He is offering you a system that does meet the performance specification you gave. It’s just that your specification was incomplete, so you inadvertently left the door open to buying the wrong product.

Professional vendors will ask you, as they want to see their systems perform well for you. But the fact remains that in preparing a design and specification for a project, you have to look deep into the whole process, not just whether the design will work as intended but also how it will be built, or even if what you designed can be built; and you need to do that from the start, not when you are ready to buy because how you buy affects what you buy. Proper and thorough specifications are the best insurance—for you and the vendor.

Jack C. Cox, P.E., is director of engineering at Edgewater Resources. He can be reached at jcox@edgewaterresources.com.

| Categories | |

| Tags |